Behavioural Cybersecurity Pt 3: The research context: clicking on dodgy links

So this is the third in a series of posts delving into behavioural Cybersecurity. We started with a general overview of how people keeping themselves safe from cyber attacks is surprisingly similar to people keeping themselves fit and healthy. This means that we can apply really well researched, empirically derived models of health behaviour to cyber for a really deep understanding of what barriers there are to people carrying out ideal behaviours. In part 2 we delved further into some of the main psychological models in the field to understand exactly how people’s motivations and attitudes could predict outcomes. And now we’re going to walk through how we formulated our main research tool – a questionnaire that we deployed to staff within a major Australian bank – and what we hoped to find.

So during this project, the primary research question at the time within the the bank was – ‘why do people click on dodgy links?’. (And perhaps not surprisingly this is still a burning issue right across the commercial world.)

You can imagine that staff working at a bank clicking on Phishing emails and having their computers, within the bank networks, being compromised is of major concern to their security departments.

Usable Security – Long in the tooth?

At the time, the dominant behavioural security paradigm at the time was ‘Usable security’, which insisted that if you made things easy enough for users – they would carry out desired behaviours. But this philosophy was beginning to get somewhat long in the tooth, and we had witnessed an industry-wide drop off in effectiveness of mitigation effects based on these ideas. We were making things super easy for users – but they were still carrying out risky behaviours. A lot.

Fake Phishing – Evaluating Security Behaviours

At this point it is worth noting that a common practice amongst large corporates with engaged cybersecurity capacities is to evaluate the level of security behaviours in their own staff by sending them ‘fake’ phishing emails – and then measuring the response.

Data is often then tabulated and you get data that managers love such as ‘this department’s click-through rate is 34% and this one’s is 29% etc…’.

Frequently these exercises are carried out by an external company such as Pishme.com – who are provided a list of the email addresses of staff by the company itself – PhishMe.com then out send out phishing emails to those staff, see who clicks, and then deliver back a report to the security department.

Test Results

Which, from a research perspective – is incredibly cool. Here you have a single, neat, easily measured, behavioural indicator: a binary (did click / didn’t click) response, which you can deploy exhaustively to the population in question, in a real world environment. This is a beautiful and rare opportunity in behavioural / cognitive research.

The current body of literature around this issue at the time consists almost entirely of the usual test populations of “32 undergraduates of the university of Michigan” etc… so the opportunity to do real, situated research with a response set of thousands of participants was amazing.

But I don’t want to discuss the quant side of this project here. Rather, the first stage of this research was qualitative – a kind of broad discovery-type phase centrally focussed on a number of staff interviews – to determine what the general attitudes, practices and beliefs around cybersecurity in the workplace were – which would then inform which psychological variables and parameters we might deploy in the later, more quantitative methods. This was an enormous challenge from a security and privacy perspective.

- We had to develop custom data anonymisation code that we remotely deployed within the Bank’s systems (technical nightmare) before we could get access to the data.

- We had to convince our human research ethics board that this research, utilising deception and which did not employ full consent from the participants (typically anathema to research ethics boards) was defensible.

- We had to develop elaborate privacy protocols and security theatre around the identity of the participants and ensure them that their participation was completely anonymous (as we carried out the interviews – we didn’t even know their names!) so that they could speak freely and openly.

But we doggedly worked through all these institutional issues and ended up carrying out a series of interviews which gave us an amazing insight into the lives and thoughts and motivations of bank staff as they deal with cyber attackers every day in their work.

This all turned out to be well worth the effort.

Analysis, Findings, and Insights

We developed a list of questions initially based on our extensive reading of the existing academic literature on the subject of cyber behaviours and specifically phishing victimisation. We wanted to tap into the cognitive variables that had already shown to be important determinants of cybersecurity behaviour – but rather than just measure, for example, ‘Self Efficacy’ we were aiming at a deeper, richer understanding of how these variables reflected people’s lives.

But since this was an exploratory / discovery type project, we also had a few hunches we were interested in exploring and also wanted to leave a large amount of flexibility – so that if we discovered something new and interesting, we could dig down into it. Thus our initial research instrument – the questionnaire – was extensive. There was so much we were interested in knowing.

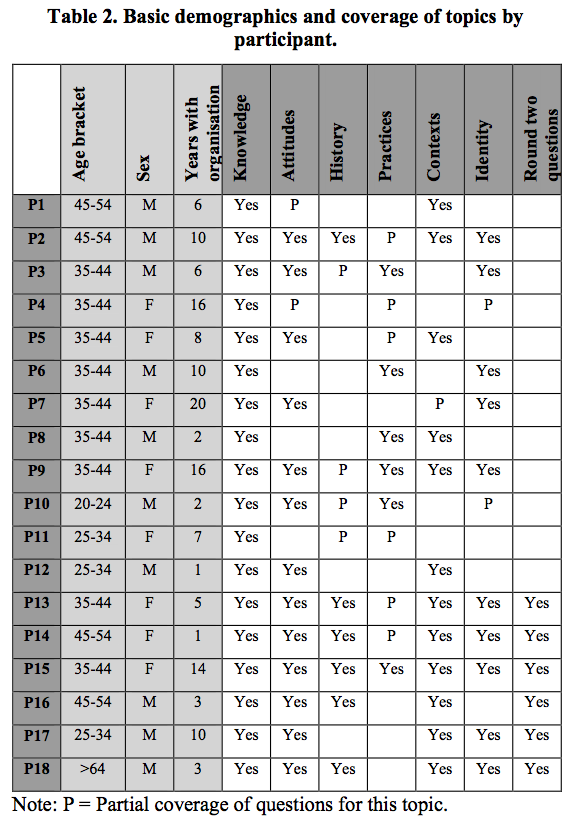

But then I realised – that since most qualitative methods suggest that 4-6 participants is a often enough to achieve ‘saturation’, we could divide up the questions and administer some of them to different sub-groups of participants – thereby getting far wider spread of content. However we also earmarked some of the more important and foundational questions to be asked of all participants, and thereby came up with a nice compromise of both breadth and depth of interview topics.

The Question Categories

Once we had our master list of questions we divided them up into the following categories, each with about 6 questions in them:

- Knowledge – we were interested in the participants level of knowledge about both cyber practices generally and how it was deployed at the bank.

- Attitudes – Did they value being secure? Why is it important? Do they feel vulnerable to threats?

- History / experience – How have they learnt about cyber? Have they previously had a negative experience and how did it effect them?

- Practices – specifics about passwords, questioning emails, reporting dodgy links, and how they engaged with the cybersecurity information channels at work.

- Contexts – How do they work with email, are they stressed, do they talk about cyber with other people, are there consequences of poor cyber behaviour?

- Identity – Do they see themselves as equipped to deal with cyber threats, who’s responsibility is it to protect the bank, and whether it’s important to them to be able to carry out good cyber practices.

About halfway through the interviews, since we were debriefing and doing preliminary analysis as we went, we made a few interesting discoveries. We thought that some of these might lead to powerful insights so we added a further set of questions to probe these preliminary findings. These were around various topics such as:

- Changes in email practices according to how busy they are.

- How their attitudes to cyber differ at work from at home.

- How they engage with the cyber security team within the bank.

These became an additional set of questions delivered to subjects in the second half of the interviews.

The entire research questionnaire, if you’re interested, is available here.

Stay tuned for the next blog post – coming soon – which will start going through the results – some of which were wildly surprising and suggested entirely new approaches to staff education and mitigation efforts within the bank.

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889

Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889 Email:

Email: