Behavioural Cybersecurity Pt 4: Findings – Creating champions of change

Today we’re going to dig into a fascinating discovery of how people react after having been scammed on-line. Or specifically how the way they communicate about it often falls into one of two very different styles of behaviour – and which one they exhibit depends on a completely different variable – how much they perceived themselves as technically literate.

Previously we covered a general discussion about what health psychology offers the field of cyber security behaviour, some stuff about psychological models of behaviour, how we tackled the research questions from our client – a major bank – and now this week we’re going to start talking about the actual findings from our research.

A little bit more about the research tool.

So the interview format that we delivered was semi-structured, meaning we had a number of specific questions that we would ask, and then often follow up responses with deeper ‘probing’ questions to elicit more detail or extend our understanding of the participants experiences – but we also allowed the participants to just talk. Sometimes these unstructured parts of the conversation drifted into fascinating areas that we had little idea that would be valuable at the outset of the research. We guided, and facilitated, and added structure – but also followed, were flexible, and dug into whatever promising leads emerged in these rich, extensive, revealing conversations.

We were at first concerned that participants would exhibit a lot of ‘social desirability’ bias – ie: would not be particularly truthful in order to not look stupid, or lie in order to hide poor security practices – but, after carrying out really elaborate ‘security theatre’ to ensure the participants understood our commitment to their privacy and data anonymisation, for almost every interview – we found participants were willing to volunteer mistakes and what they knew to be bad practices and discuss them pragmatically and with a high degree of emotional honesty. While we can never be sure that some things weren’t covered up or glossed over, we felt that we were provided with a startling level of honesty and insight into the participant’s practices and understandings about their security practices. EXCEPT IN ONE CASE – which we’ll get to later.

I am not going to talk about the analysis here in these articles since it’s a bit nerdy and not particularly interesting to those who aren’t social researchers. Instead, let’s get straight into the findings. Because there were a LOT of findings. The first one we’ll cover today.

Communicating after a bad event

A lot of research has been carried out into how negative experiences change behaviour – and often with mixed results. People seem to exhibit a complicated array of responses to ‘getting their fingers burnt’. But since this has been discussed as a possibly important determinant of behaviour, we asked people a few questions about whether they had experienced security breaches or ‘been hacked’ or similar problems. We set up a series of follow up probes to ascertain, if so, what was their response, how it made them feel, and whether they thought it had changed their behaviour. We discovered a number of our participants had had some form of negative experience and, as we suspected, and that there was a lot of variation in people’s responses to this, ranging from ‘I haven’t changed anything since – it was just ‘one of those things’’ – to: ‘Oh yes, I changed a lot of things after that’.

Two different types of people

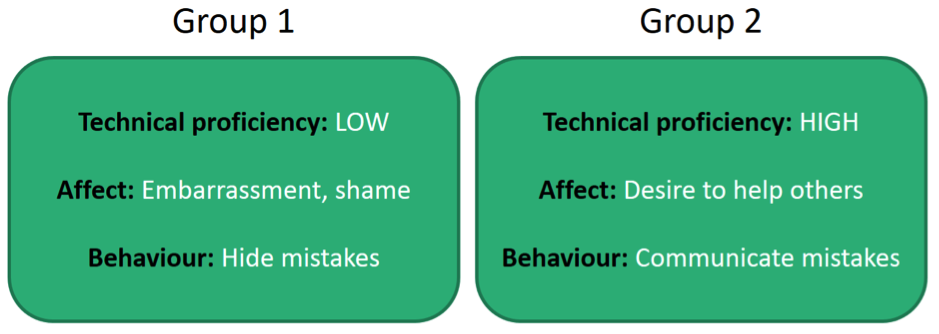

While analysing all these responses, and trying to grapple with people’s responses to a crisis like this – I suddenly noticed a really interesting pattern in the responses. Within all of our participants we had really nice, wide array of technical literacy. We had one or two very senior IT staff, but also a bunch of front-desk operators, or marketing staff etc… who were definitely not ‘computer whizzes’. And what suddenly became clear when looking at the responses – was that those who saw themselves as being not very technically literate, were deeply ashamed of what had happened. They didn’t talk about it with people. They didn’t report it to their IT department. They found it embarrassing to discuss with us and exhibited a lot of classic signs of emotional discomfort, (such as sudden little bursts of laughter) when discussing what had happened. They definitely did NOT tell stories about it in the lunch-room.

On the other hand – the participants who had a high degree of confidence in their technical skills, were far more forthcoming about their incident. Their immediate response was often to tell those they were socially close to about it, and frequently posted the information on intra-net channels and within their bank’s networks. They did this, seemingly driven by two reasons. 1) they were fascinated (and even faintly admiring) about the fact that they had been taken in and were interested in discussing it. 2) they were highly motivated to warn others about it so that it would not happen to their colleagues and friends.

What this means – how to find and create ‘Champions of change’

This has really important implications for security departments trying to create good security culture within an organisation. A major thrust of awareness campaigns within organisations nowadays is creating ‘agents of change’. Identifying staff who are likely (or already are) to evangelise a value system on your behalf, model good behaviour and drive change from within their local little pocket of an organisation. With this in mind – it would seem that ‘passing the mic’ to those with high levels of self-confidence about their technical skills – and providing them with a platform to discuss their experiences and problems would be an excellent avenue to drive cultural change from the bottom up. Because most people don’t like talking about failures – or experiences that make them look stupid or careless.

Stay tuned for the next post where we present more findings – this time about how best to help people learn more – when they’re looking for answers about cyber security.

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889

Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889 Email:

Email: