How to talk about Covid-19. Morrison vs Andrews

So right now, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, Australia is facing one of its biggest public threats to public safety since World War 2. The fear and uncertainty out in the community is palpable and it’s at moments like these where people typically look to leaders for clear communications that both inform us about the threats, and motivate us to respond in the best way we can.

Same crisis – two responses

A LOT has been written about our federal government’s response to the crisis and especially its seemingly slow and sometimes apparently confusing and contradictory statements and actions. I have to say; watching our prime minister’s public address to the nation on the eve of a completely unprecedented national emergency had me somewhat concerned. Morrison’s communications seem to be, well at the very least, ambiguous and unfocussed. Now interestingly, a speech by the Victorian premier Dan Andrews, given on the very same day, seemed to hit every single one of the major elements that we want to hear from a leader. I felt motivated, I understood more about the threat, and reassured that things were serious – but we would cope.

To understand why one speech worked and the other didn’t, I decided to analyse these two speeches using empirical methods taken from public health psychology.

Public health communication – the Psychology

So today, we’re going to take a brief break from talking about psychology of cyber security, and delve into an amazing, and topical, example of public health communications. Because as we’ve talked about previously, mass behaviour change in the pursuit of better health outcomes of people is a field that is well researched and we know quite a bit about. We understand what values in people’s heads will prevent them, or conversely encourage them, to undertake good health behaviours and there is an established and dependable body of knowledge about how to communicate in ways that elicit these behaviours.

So what should good health communication look like? Well it should address particular aspects of our beliefs (in the psychological jargon these are called constructs – presumed variables in people’s minds that can vary one way or another) that have been shown to influence behaviour. For example one construct might be ‘Belief in a higher being’. It’s something you could measure via a survey or similar, is known to effect certain behaviour, but is essentially just a hypothesised variable in someone’s mind. This is a construct.

The Theory of Reasoned Action

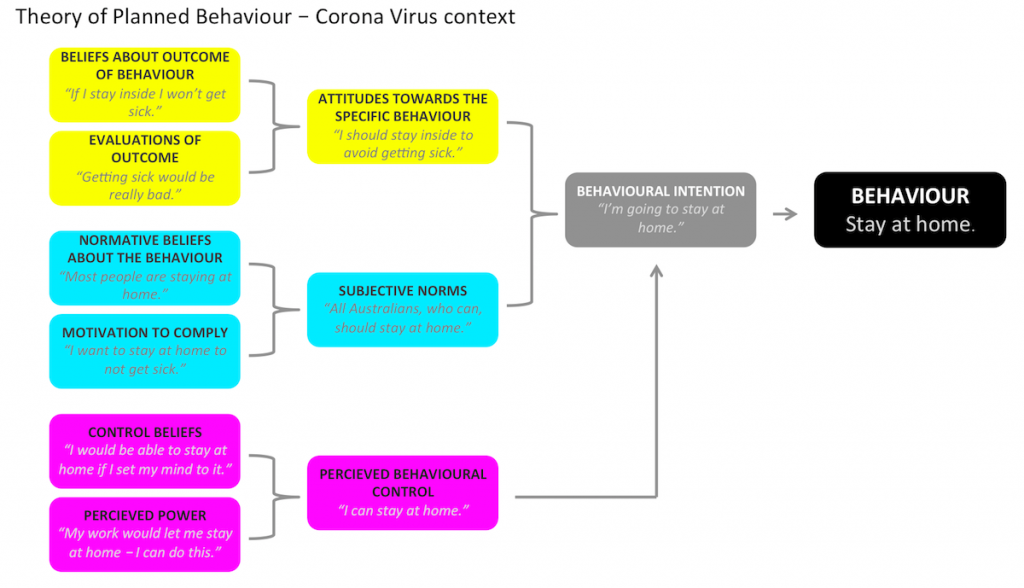

Probably the most well tested and influential psychological model in health psychology is the Theory of Reasoned Action. Developed in the 80s and vigorously tested by thousands of researchers over a myriad of different scenarios and contexts ever since, it specifies that there are a number of very specific mental variables – that all need to be aligned – before people are likely to take on a desired protective health behaviour. Have a look at the image below.

All the boxes on the left are mental variables that need to be in the correct state before boxes further over on the right are activated until eventually leading to the intended behaviour on the far right. So:

Attitudes towards the intended behaviour

People need to believe that the behaviour will actually address the problem and that the outcome is desirable.

What we think other people are doing (Subjective Norms)

People need to believe that most other people around them also carry out the behaviour and they need to have motivation.

Do we think we can do it? (Perceived Behavioural Control)

People need to think that nothing in the outside world is stopping them from carrying out the behaviour and that they have the internal capacity to carry it out.

It’s only if all these variables are aligned that a person is likely to take the intended actions.

The two speeches

So with all this in mind, let’s have a look at these two speeches and see how they stack up in terms of complying to what we know about effective health communications.

The original two speeches are here:

- Here’s Scott Morrison’s national press conference on the 22nd March. It’s 1773 words long.

- And here’s Dan Andrews’ press conference on exactly the same day. It’s a bit shorter – only 1063 words.

I got hold of transcripts of the two speeches and then isolated all statements that fell into each of the three mid-level categories within the TRA identified above. Ie: Attitudes towards the behaviour, Subjective Norms (what people think other people are doing), and Perceived Behavioural Control. I wanted to see how the two speeches stack up in terms of addressing the known variables that people need to have activated in order to change their behaviour.

Attitudes towards the desired behaviour

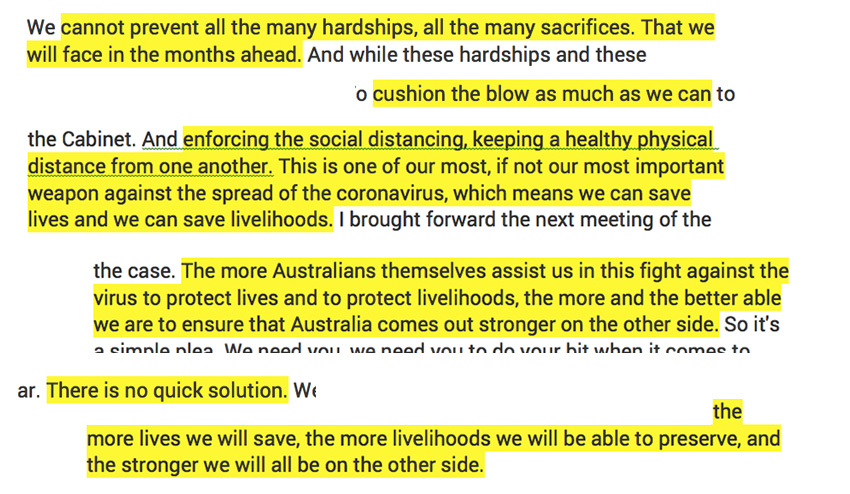

Let’s start with attitudes towards the desired behaviour. Here we want to hear statements that clearly lay out the value that the desired behaviour brings to a person and that the behaviour is positive and will be effective. All of Morrison’s statements to do with these types of concepts are shown below.

As we can see that many of these statements are decidedly negative, even fatalistic about the desired behaviours. The fact that the first mention is ‘cannot prevent all the many hardships…’ sets a strong scene of the inevitability of bad consequences and is likely to immediately sap any kind of will to take radical action about it. Furthermore the direct consequences of good behaviours are often referred to in highly abstract terms ‘Australia comes out stronger on the other side…’ – there is very little in there that lays out in concrete terms why us taking precautions will positively affect our family and loved ones.

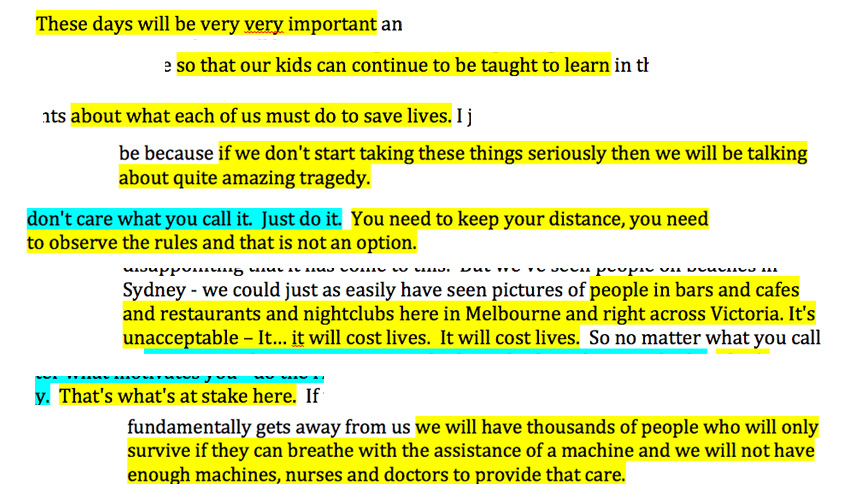

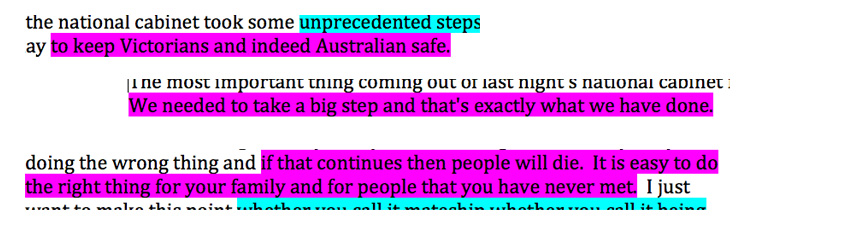

Let’s contrast this to the equivalent statements pulled out of Dan Andrews’ speech.

Dan Andrews’ statements could not be more clear. They highlight the importance of the situation. They link these consequences directly to our immediate families and paint an immediate and clear picture about the impact of the behaviours that we want to see. This is a total contrast to Morrison’s speech.

The behaviour has to be seen as ‘Normal’

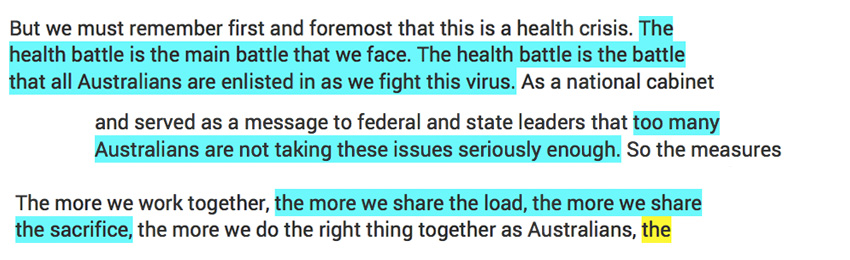

It’s been shown that a really important antecedent of behaviour change is people thinking that it’s ‘normal’. That is, that everybody does it. This is what the term ‘subjective norms’ means. Therefore it’s really important for messaging to emphasise that everybody around you is carrying out the desired behaviour. Let’s have a look at our two speeches and see how they stack up on this aspect. Firstly Morrison:

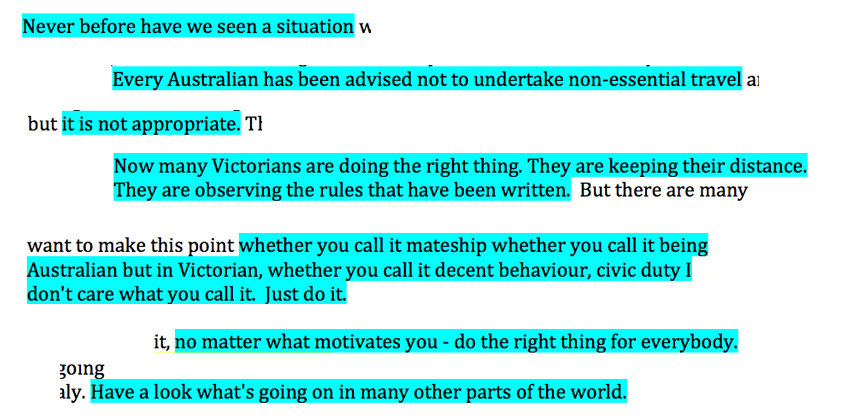

It is interesting to see that in the two examples where Morrison does lay out the collective response required to combat the threat (first and third statements) – he uses highly abstract, and, to my ears anyway, kind of ambiguous, indistinct language. While in the middle statement immediately destroys any idea of an emerging norm of good behaviour. Let’s compare this with how Andrews’ statements reflect the desired group behaviour.

The first thing to notice here is how much MORE content is to do with what other people are doing, despite being a shorter speech than Morrison’s. This is clearly a real focus of his entire outlook – and as the model demonstrates – understanding that others are in the same boat as you, and are doing the same things, is an essential component of changing your behaviour. Furthermore, we can see that in several instances there are very clear behavioural outcomes stated. It’s clear what we are expected to do. Finally – he doesn’t just invoke our immediate neighbours – instead he frames our actions, at the end, in the context of the entire world. And as the TRA, and the entire body of health psychology literature again and again has shown, understanding that others are in the same boat as you and are doing the same things, is an essential component of changing your behaviour. Powerful stuff.

Do we think we can do it?

Finally, it has frequently been shown that unless people think that they have the capacity to carry out a behaviour, they are unlikely to try to do so. If you think quitting smoking is just too difficult – you’re unlikely going to actually have a go. These kinds of sentiments are what is meant by ‘perceived behavioural control’ – which is made up of two more finer grained variables ‘control beliefs’ and ‘perceived power’. Let’s revisit our two speeches and see if our speakers reassure us that we have it in us – and that it’s easy to carry out the desired actions. Firstly Morrison:

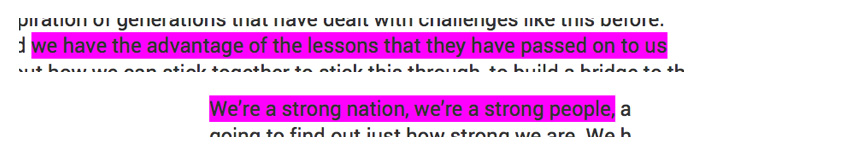

So he mentions something that qualifies as addressing this construct twice – and it’s not bad. It’s definitely in the right direction, but it is, again, quite abstract. Vague even. And in the first instance – he isn’t talking about his listeners – the Australian people – he’s talking about the government – which seems to occupy a more central place in his speech generally than the population he’s addressing. Let’s look at Andrews’ now:

And here we have exactly the kind of messaging that the TRA requires. Saying ‘It’s easy’. We’ve done the things required. Reassuring people that the changes are do-able and are being done. Nice work.

How could Morrison be better?

Hopefully this has been helpful. I think many of us have been frustrated and confused by many of our PM’s communications – both generally – but also specifically in the face of crises – such as the one we’re facing right now. This post should explain a little bit about why we’re frustrated, and why his style of communicating falls so far short of what we really need. It shouldn’t be that hard to write a speech that addresses the real needs of Australians at this time of crisis. There are known ways of doing this. Perhaps, in summary, Mr Morrison should spend just a little bit more time taking advice from people in public health.

Next week we’ll return to the ongoing series of posts about human behaviour in cyber security, but in the meantime… good luck out there and… stay at home.

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889

Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889 Email:

Email: