Behavioural Cybersecurity Pt 2: The Models – TRA and TPB.

So previously I talked about health psychology and what it had to offer the domain of cybersecurity behaviour. I mentioned that there were a number of psychological models which have turned out to be incredibly applicable to understanding and predicting why people do and don’t carry out good cybersecurity practices. So today we’re going to dig into some details and look at what some of these models consist of – and what they offer – and specifically – how they can be applied to the problem of getting people to exhibit better cyber behaviour.

We’re going to discuss two really big models in the field:

- The Theory of Reasoned Action

- The Theory of Planned Behaviour.

So just to recap: The fundamental aim of a psychological model is – understanding what predicts people’s behaviour. Because once we understand this, we can design interventions that reliably influence people’s behaviour. That’s the game really.

A psychological model describes the underlying processes by which our brains work, and it can be tested empirically. A good model will give you the power to actually influence people instead of just ‘shooting in the dark’ and hoping something sticks. And some of these models, the ones that have been tried and tested and incrementally improved over decades now, not only have really good predictive power – but also some quite surprising qualities. You may be amazed at some of the actual determinants of what prompts people to action.

Theory of Reasoned Action – The original

Let’s start with a look at an early and hugely influential model that really did go about changing the course of behaviour research forever.

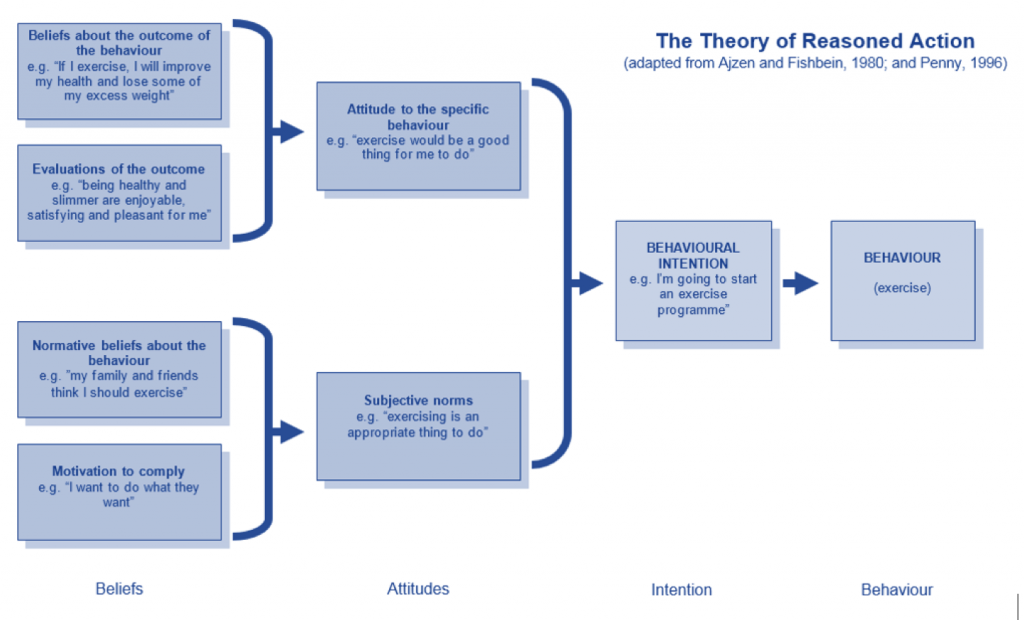

In 1980, two American psychologists who went on to become giants of their field, Martin Fischbein and Icek Ajzen, proposed a model called the Theory of Reasoned Action (hereafter referred to as the TRA). It attempted, within a health context, to explain the relationship between people’s attitudes towards a behaviour – and whether they carried out the behaviour.

Now as we all know – attitudes are rarely tightly coupled to behaviour. A person may believe eating well and exercising is virtuous and good for you – but they are also quite likely to be distracted by the offer of pizza and beers on a Saturday night. So this model attempted to grapple with one of the most challenging conundrums facing human researchers – why do people so often fail to do what they say they want to do – or even think is really important!

The TRA proposes that people carrying out a given behaviour is dependent on a number of variables. In this case cognitive variables, or beliefs and attitudes and intentions about the behaviour in question. The short explanation of the model might be – if people don’t have all these necessary precursors – they are unlikely to carry out the action.

A visual representation of the model is shown below. Have a look at each one of those boxes. The TRA suggests that the cognitive variables on the left – ‘Beliefs’ – have to be in a certain state before successfully feeding up to the next level – ‘Attitudes’ and ‘Subjective Norms’ – and these two components then contribute to whether someone intends to carry out a behaviour – which is, in turn, the best predictor of whether they actually DO carry out the behaviour in question.

Let’s have a look at some of what these cognitive variables are.

Beliefs about outcome: Does the person in question believe that the behaviour will actually result in something. Will exercise actually result in weight loss? People are unlikely to carry out something if they don’t think it will achieve their goals.

Evaluations of outcome: Is the outcome of the behaviour valued? Is losing weight a good thing? People are unlikely to carry out something if they don’t think of the outcome as positive.

Normative beliefs: This refers to what other people around them believe. The social aspect. If the behaviour is socially not accepted – again – people are far less likely to carry it out.

Motivation: is also important. Does the person actually want to loose weight?

Once all these variables are aligned, people are likely to have an intention to carry out the behaviour – and this, the model suggests, is the strongest predictor of whether the behaviour will actually take place.

The power of a model – what use is all this?

At this point let’s take a bit of a side-step and talk about what these variables actually mean. These are suggested ‘things’ inside a person’s brain. Often referred to as ‘constructs’. We can’t prove that they are there, but, after lots of research and testing, have found them to be useful and functional. And, most importantly – they can be measured.

You can devise tests – typically survey questions- that can measure these constructs. A number even. You can quantify them. So a person might have a really high value, 5 out of 5 for Normative beliefs, Motivation and Evaluations of the outcome – but have a low value, 1 out 5, for Beliefs about the outcome. ‘Nah – that wouldn’t help me at all’. This model suggests that this would be a problem and the desired behaviour is unlikely to occur.

Which means – if we measured someone, such as with a survey or interview, and they came up with results like this – we would know exactly what intervention we would need to carry out in order to increase they likelihood of their carrying out the behaviour. We would need to target their ‘Beliefs about outcome’. We would need to convince them, specifically, that the desired behaviour would directly affect and help them. Similarly, if they scored low on the ‘Normative beliefs’ (‘But no-one actually does this do they?’) then you would need to focus on this particular aspect in your messaging in order to change behaviour.

Can you begin to see the power of a validated psychological model?

And specifically, I have on many occasions, been able to apply these models in the real world – by gaining insights into people’s beliefs and cognitive variables via standard interview and survey techniques. And these insights, while often not immediately apparent, are actionable – which then have gone on to inform mitigation approaches and messaging strategies to change people’s behaviour. En-masse. This stuff works.

Theory of Planned Behaviour – The remix

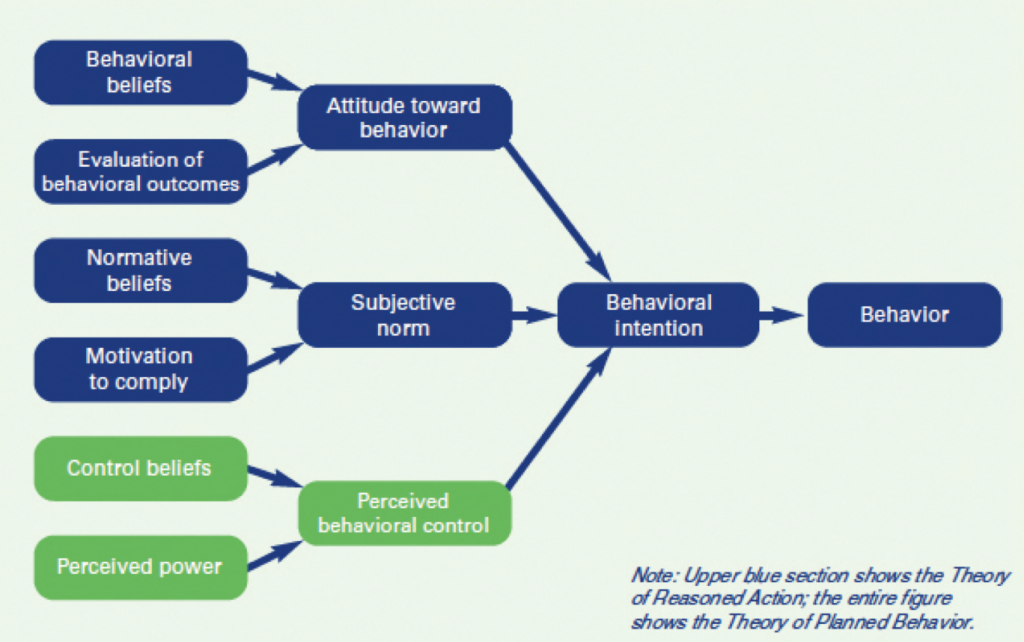

So back to the TRA. A few years after this was published, it became clear that there was a significant source of variance in the outcomes that the model couldn’t explain.

So Azjen went back to the drawing board – and uncovered a really important additional variable that also is hugely important in influencing the likelihood of a given behaviour. Namely something called ‘Perceived behavioural control’.

What this means is whether people actually believe that it is within their power to carry out the desired behaviour. As an example – someone may think that quitting smoking is good, that most people don’t smoke, and they may even really, really want to quit – but… if they don’t think they are capable of quitting ‘I’ve tried before and failed – it’s just too hard’. Then they are unlikely to even start trying.

So in 1985 Azjen published an updated version of this model, now called the ‘Theory of Planned Behaviour’. The TPB. And this has gone on to become one of the most important psychological models of all time. It can be applied to lots of lots of domains ranging from tourist travel, the success of advertising campaigns,

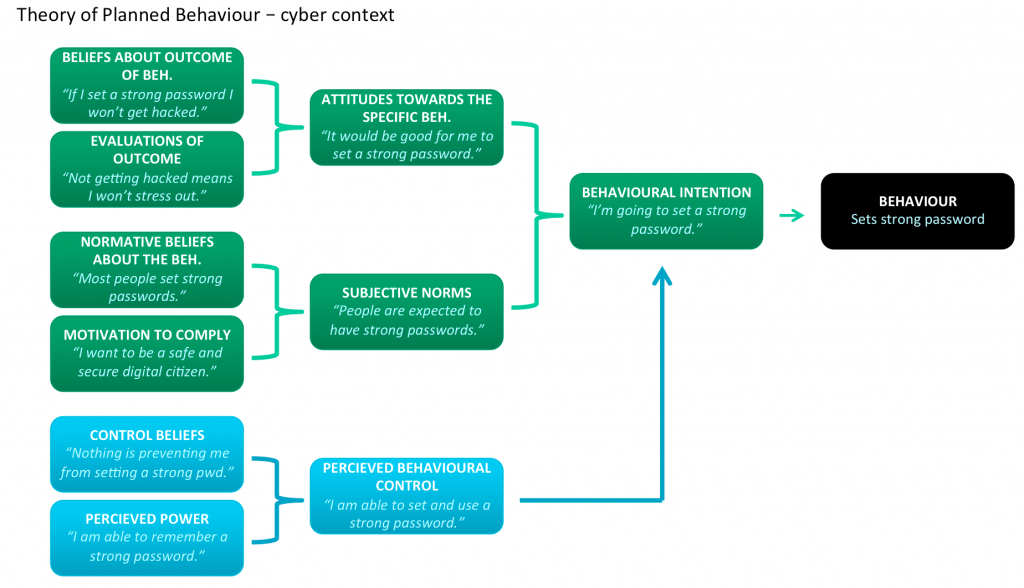

Let’s have a look at an example of the TPB in a Cybersecurity context – specifically relating to the intended behaviour of keeping strong passwords.

So as you can see, some of quite important predictors of behaviour are interesting and often overlooked cognitive variables such as perceived power. If people don’t think they can remember lots of passwords – or have an alternative method of dealing with them – they will not deploy them. No matter how much you tell them to do so.

Some key takeaways

- Merely providing information is rarely helpful in changing behaviour. You have to change people’s beliefs about themselves, the people around them, and their level of control over their lives.

- People need to feel that they CAN carry out a desired behaviour before they’ll even try – so emphasise empowerment in your messaging.

- People need to feel that the desired behaviour is socially acceptable – or even expected before they are likely to do it.

- If they don’t WANT to do it – they are unlikely to.

And finally – until you measure all these variables – and understand what are the major cognitive impediments to people taking action – you are unlikely to achieve mass behaviour change in your interventions.

Further reading

Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour

This is a classic study utilising the TPB to evaluate people’s Information Security practices. It’s a great example on exactly how you can understand the thinking of a cohort of people and how the model explains their behaviour.

Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predicting online safety behaviour

This is a terrific paper (but quite academic – be warned) that specifically looks at the variables the TPB added – those of self-efficacy. Ie: whether people believed they could carry out the desired behaviour. This is an often overlooked factor in Cybersecurity mitigation approaches – and this paper does a really good job of showing, comprehensively, how important these beliefs are as a predictor of behaviour.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/087b/1b537a71b2364cabba049e204d72d596384f.pdf

Review of behavioural theories in security compliance and research challenges

And finally, this is an excellent round up of a whole host of the main psychological / behavioural models that have been applied to cybersecurity.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/087b/1b537a71b2364cabba049e204d72d596384f.pdf

And stay tuned for the upcoming chapters in this series on Behavioural Cybersecurity including posts about:

- Models that apply to behaviour in response to Phishing emails.

- Applying these models in the real world – a case study.

Thanks for reading!

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889

Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889 Email:

Email: