Bondi Junction interchange, emergent behaviour and escalators

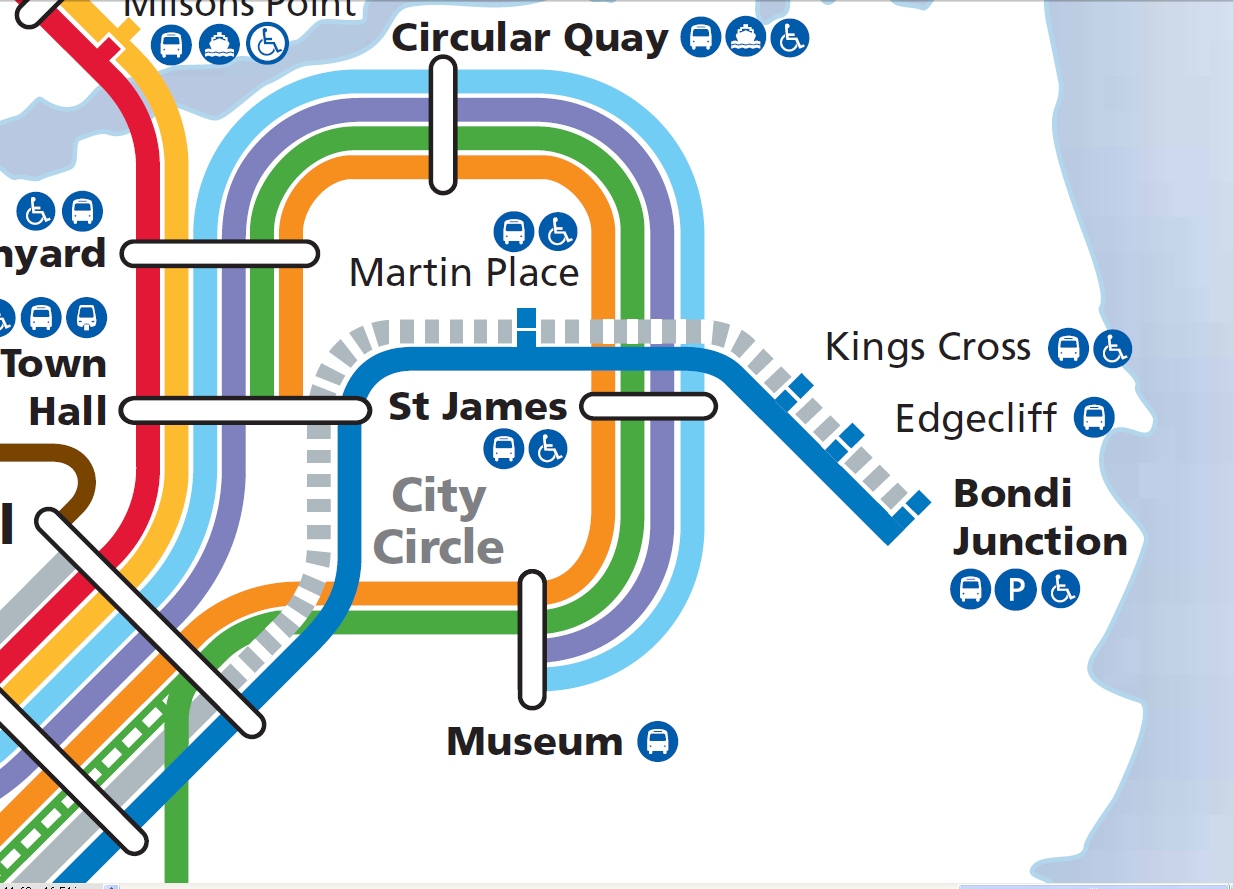

Haha! This is terrific. A nice clear explanation of a phenomenon I have been observing and thinking about for a while – saves me having to write it all up. So I’m living in the Eastern suburbs right now, which means I frequently travel through Bondi Junction transport hub using public transport on my way to and from the city. And the interchange is a kind of amazing place. I am fascinated by locales of high density – in whatever sense – and observing the patterns and behaviour that density creates. Specifically – thousands of people per minute pour through the bus/train interchange there on their way to work in the mornings, and then home again at night. And (despite the lack of development and poor Public Transport funding over the past many years) it kind of works… it’s a system most people know well and it quite effectively funnels people along their chosen routes.

But there are a few places where it can go wrong, which are of course the most interesting bits. Specifically there is a massive choke-point between the bus interchange and the underground train station that consists of a single pair of standard width escalators – one going up, one going down.

Now, Sydney has, over the years, become pretty good at the ‘stand on the left, walk on the right’ protocol of escalator use – which is terrific – and worthy of its own article – a self-organised, socially normative group behaviour shaped by parallel technology use. But this particular escalator, at peak times – sometimes grinds to a complete stop with a continuous crush of commuters in both ‘lanes’ of each escalator standing completely still and waiting to be delivered at the top. Frustrating. And you can see it on people’s faces – the ‘Oh no – the walk lane has come to a halt’ look of despair as they join the throng. And of course, once it has come to a stop – it’s almost impossible to start moving again until the pressure reduces.

Now, Sydney has, over the years, become pretty good at the ‘stand on the left, walk on the right’ protocol of escalator use – which is terrific – and worthy of its own article – a self-organised, socially normative group behaviour shaped by parallel technology use. But this particular escalator, at peak times – sometimes grinds to a complete stop with a continuous crush of commuters in both ‘lanes’ of each escalator standing completely still and waiting to be delivered at the top. Frustrating. And you can see it on people’s faces – the ‘Oh no – the walk lane has come to a halt’ look of despair as they join the throng. And of course, once it has come to a stop – it’s almost impossible to start moving again until the pressure reduces.

Right. So after observing this phenomena closely for some time I think I know why this happens. It’s because some-one in the ‘walk’ lane stops walking – even if just for a moment. And it almost always starts right near the top – in the area where the escalator flattens out. As simple as that. Next time you’re near an escalator watch what people do as they near the top. Not everyone – but a certain small proportion of people – quite consistently stop walking as the escalator flattens out and just before they need to step off and continue walking on normal ground. It’s interesting – not everyone does it – but there is a significant proportion of people (say one on 10, maybe one in 20) who do. I could speculate as to why this is – Indeed I wonder if it is a brief ‘rest’ induced by the perceived ‘rest’ that the escalator exhibits after having hoisted them up that vertical distance – which would be a truly amazing instance of mirror neurons, anthropomorphism and more evidence of how we imbue inanimate objects around us with assumed agency and motivations (more on this soon when I write about Clifford Nass’ book ‘The man who lied to his laptop’). Alternatively the answer could be more prosaic and that people are simply preparing themselves for the tricky little step at the end of the ride when they have to step onto solid ground again. Regardless…

I am convinced it is these people who ‘stop at the top’ who bring the entire (otherwise highly efficient) system to a grinding halt. This has to do with emergent behaviour in ‘traffic’ like situations – and has been discussed and modeled for years in terms of traffic flow. I’m sure most people are aware of the phantom ‘accidents’ on busy motorways where traffic suddenly slows down for a period and then speeds up again – almost as if people were slowing down to look at an accident by the side of the road – when in fact – no accident actually took place. This kind of systemic phenomena is discussed a lot in traffic management circles – and there are various other cool and interesting things that happen in these environments – such as phantom ‘waves’ of slow speeds that travel up and down the travel path. This idea is discussed in this terrific article called ‘Traffic Waves’ by William Beaty here…

It is this same phenomena that brings the escalator ‘walk’ lanes to a stop. As one person pauses at the top of the escalator, the person behind them has to stop too, and – depending on the ability of the spaces between people to ‘buffer’ a temporary interruption like this – which decreases with density – this local area of non-movement will not only continue but also propagate back against the direction of flow until the people getting on the bottom of the escalator are stationary too. Ie: total grid-lock in the ‘walk’ lane.

So… what to do about it? Short of a massively funded advertising and population awareness raising campaign through all major media channels (unlikely) – there may be some (more prosaic) approaches to fixing this problem.

1/ Signage. ‘Don’t Stop at the Top’. Maybe a series of signs placed around the interchange. But more specifically on the escalator itself, in the gutter between it and the other escalator – where people walking can clearly see it.

2/ Minimise distractions at the top. How to do this – tricky. Perhaps the most important thing is to try and reduce visual distractions such as timetable displays etc… near the top of the staircase so that people aren’t distracted and stop to look at something. And of course, this would be a common feature of the top of scalators when a whole new vista is suddenly in view – so perhaps if designing from the beginning – have a section of tunnel that continues past the top of the escalator so that people cannot see what is coming up until they are off the end.

3/ Incentivise walking at the top. Hmmm… tricky. What would universally motivate people to continue walking at the top? I guess to answer this question you would have to carry out some user research to discover ‘WHY’ people stop at the top. If my (above mentioned) hypothesis is correct – and that stopping is an anthropomorphic sympathetic response to the escalator doing less work – we would need to somehow extend the impression of the escalators ‘work’ once on flat ground. Perhaps engine noise? So as one nears the top one begins to hear a powerful engine grinding away and therefore implies the work required to pull all those people up the slope? This would be a terrifically fun hypothesis to test.

So here is a clear need for user-testing/research. ‘WHY’ do people stop at the top? Because really, all these suggested mechanisms for addressing the problem are really kind of ‘pie in the sky’ until we have a clearer idea of why people do this.

In the meantime, remember folks, if you’re on a crowded escalator – don’t stand in the ‘walk’ lane – and most importantly: Don’t Stop at the Top!

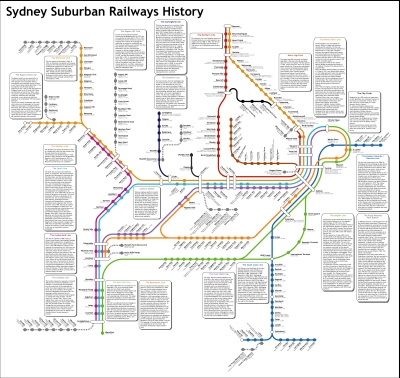

Oh and for those interested in public transport infrastructure – check out this AMAZING Infographic by Datazoid of Sydney’s train system history. Awesome!

Oh and for those interested in public transport infrastructure – check out this AMAZING Infographic by Datazoid of Sydney’s train system history. Awesome!

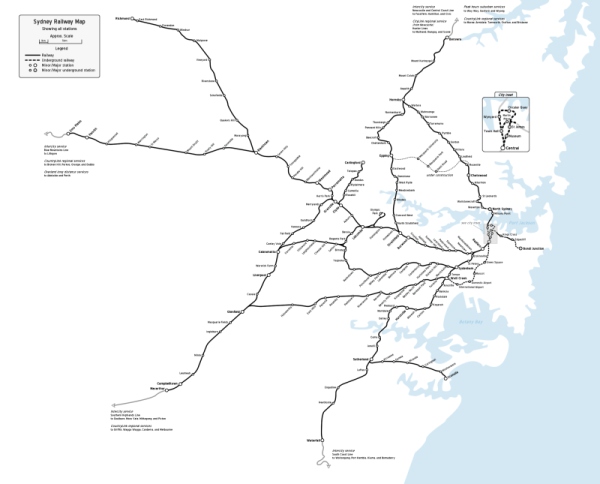

Oh and look! I managed to write this entire post without getting into ‘the map is not the terrain’ and cartography theory… Ok – just for hell of it – here’s a geographically accurate map of Sydney’s public transport train system. Barely recognizable from the neat, abstracted network map we’re all used to eh? Lovely.

Oh and look! I managed to write this entire post without getting into ‘the map is not the terrain’ and cartography theory… Ok – just for hell of it – here’s a geographically accurate map of Sydney’s public transport train system. Barely recognizable from the neat, abstracted network map we’re all used to eh? Lovely.

Updated: the link to ‘Sydney’s train system history now links to a more recent, comprehensive, and even more garganutuan version of this file – which is totally awesome. Shout out to Datazoid and his idiosyncratic collection of predilictions (such as reviewing energy drinks, talking about public transport infrastructure, and his own music) for making this thing and getting in touch.

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia

Address: 11 Silva St, Tamarama, Sydney, Australia Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889

Phone: +61 2 (0) 404 214 889 Email:

Email:

It’s pretty natural to stop at the top, or at least just before you have to step off the escalator. There are two things at play here: 1) The step at which you leave the escalator and hit solid ground may not fall into your natural sequence of ‘left right left’, so you need to recalculate that final step. and 2) Your walking speed actually changes at this point. Kind of like changing gears when you are driving a car. There are always a few moments between gears when you are not accelerating. So asking people to ‘not stop at the top’ is actually more challenging that you might think. You’re asking people to somehow calculate their final step so that it fits into their ‘left right left’ flow, as well as continue forward momentum whilst changing walking ‘gears’. Nice article 🙂

Ace! Interesting discussion 🙂

I reckon Bondi Junction interchange has heaps of design problems! From my vague recollections, the re-engineering of the whole interchange was tied to the development of Westfield, through developer contributions (s94 – in the Environmental Planning Act – there used to be a requirement for major developments to help pay for additional community infrastructure).

However, through price negotiation, the interchange lost features to cut costs. What is there now seems to de-prioritise anyone on public transport, in favour of the private vehicle. A mind set that doesn’t even recognise any commercial value of pedestrians = they might want to buy stuff too.

E.g. Where those escalators are…shouldn’t the underground walkway just carry right into the shopping centre… rather than up to street level, requiring stupid fences force pedestrians the long way round the traffic flow, and even to their own taxi rank.

So perhaps the choke point issue come from the developers not property designing for volume and cutting costs on ‘public good’ so they can spend more on the centre. That doesn’t really help so much with the current day solutions though does it. 🙂 Really they need 4 escalators.

P.s. you know where all the buses pull in at different doors, I heard (anecdotally) that the original road design was on an angle so that people could see if their bus was coming *through the window*, without constantly going outside the glass doors and standing on the tarmac. Cost vs safety, yay Sydney.

Hi! Thanks for including my Sydney Railways infographic on an awesome article. This kind of thing is right up my alley, I spend a lot of time thinking about the minutiae of what makes people tick, and why strange things happen (usually when people are involved).

I actually have a more up-to-date version of the map, with the entire Sydney/Newcastle/Nowra/Goulburn/Lithgow area mapped. I had a lot of time on my hands, once.

http://colonpipe.com/map-of-the-history-of-sydneys-railways/

Thanks again!